“Innsbruck is the city of my dreams.”

In our blog series marking the remake of “Geierwally,” we have described the early years of “Annele,” or Anna Knittel. Her youth ended abruptly after she finished her studies in Munich, when the “serious side of life” caught up with her. Innsbruck has now become her life goal.

After “Annele” had kidnapped a young eagle from its nest in the dangerous Saxerwand rock face in the Lech Valley for the second time in 1862 – her father named the bird ‘Hansl’ and raised it for sale (mostly to royal houses) – Innsbruck became the city of her “longing,” as she admitted. She also knew that Innsbruck was the only place where she could develop her artistic talents.

It was the dawn of photography, and the young painter Anna Knittel wanted to establish herself as an artist in the early 1860s. After completing numerous portraits, including one each of her patron Anton Falger and his wife, as well as her sisters, father, and mother, she found it difficult to find clients in her area who wanted their portraits painted. And so she began with a self-portrait. This painting opened the door to the Tyrolean art world for her. She sent the painting to Innsbruck on spec, “full of anxiety about what the art experts there would say,” as she writes in her memoirs. “And lo and behold, one fine day I received a thick envelope from the Ferdinandeum Museum, which had purchased the painting and sent me the sum of 44 guilders immediately.”

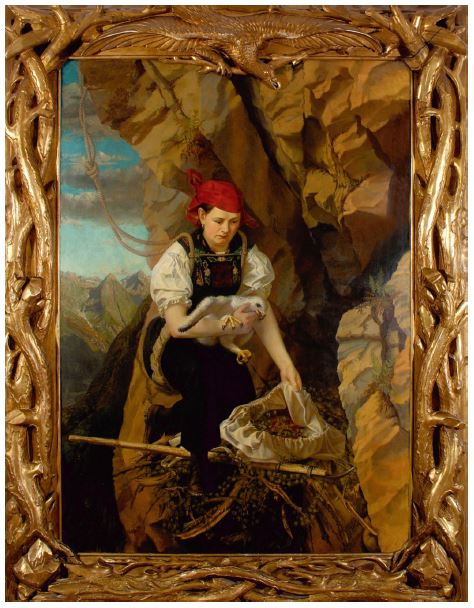

Anna Knittel's self-portrait was purchased by the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum in 1863. This first commercial success paved the way for her financial success in Innsbruck. Image: Tyrolean State Museums TLM

“...the ass of the bold Miss Knittel was not safe”

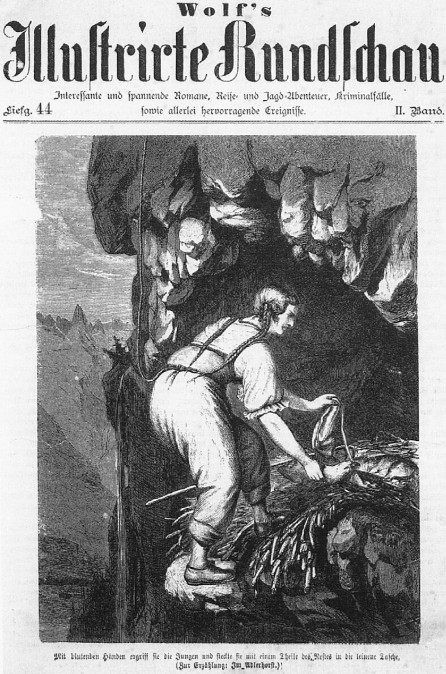

A visit by Mathias Schmid to Elbigenalp in 1863 reinforced her determination to move to Innsbruck. She was already familiar with the Paznaun painter, whom she had met in Munich. "He was very kind to me and urged me to go to Innsbruck," recalls Anna Stainer-Knittel. Schmid also promised the young woman he would find her commissions and accommodation. This is even though Anna must have been somewhat resentful towards the painter, for he had illustrated the publication of Anna's courageous deed in the Saxerwand. Her acquaintances in Munich made a bad joke about this, saying, "Schmid diligently paints farmers, monks, and even bailiffs, but he wasn't sure about the ass of the bold Miss Knittel." Anna then created the famous self-portrait that she displays in the Adlerhorst.

“Farm girl at a charcoal kiln” by Mathias Schmid. He came from Paznaun. The painter, who was already well known at the time, found Anna Knittel her first apartment in Innsbruck. Image: Wikipedia

Instead of painting Radetzky in large format, Anna painted herself.

In Innsbruck, she moved into lodgings with Dr. Brauner, a regimental doctor. She was immediately given what she describes as an "honorary commission" to paint a portrait of Archduke Karl Ludwig. And the regimental doctor's house was the perfect place for her. The Innsbruck sharpshooters were desperately looking for an artist to paint a portrait of Emperor Franz Josef's brother for the opening of the new provincial shooting range in Höttinger Au. Anna felt confident enough to take on this reasonably honorable task. She used a picture of the Archduke as a model.

Her landlord made her work easier by providing her with an original general's uniform, which she could now copy perfectly. She was also supposed to paint a large-format picture of Field Marshal Radetzky and had already covered the frame with canvas. However, the clients decided to commission only a bust portrait of the marshal. This was no problem for Anna Knittel: she wanted to correct the picture Mathias Schmid produced for the Illustrirte Rundschau anyway. A large painting shows her digging out the eagle's nest.

Mathias Schmid created the engraving that brought Anna Knittel's courageous deed to the attention of a wide German audience in Wolf's Illustrirte Rundschau. Anna herself was unhappy with the depiction and decided to counter the front-page image with a self-portrait.

Anna Knittel's self-portrait of her descent to the eagle's nest and the rescue of the young eagle in a linen bag. You can also see the most important tool used in this operation, a hook normally used to fish wood out of the river. And if you look closely at the picture, you can see a little man sitting in the lower left corner. This was probably Anna's father, who actually witnessed her courageous deed.

“I want him”: Anna finds her life partner and soulmate

In the spring of 1866, Anna lived on Innrain in the Knapp family home. Two lives crossed paths here. “A young businessman moved in shortly after she moved in,” she recalls. “He was a beginner, a formator, and had a bride in Switzerland who was rich.” He could also sing beautifully and was hardworking. A letter from the pastor of Elbigenalp would then seal the fate of two people. The letter was accompanied by another letter, which she was asked to forward to the correct address, which the pastor did not know. The letter was addressed to Engelbert Stainer.

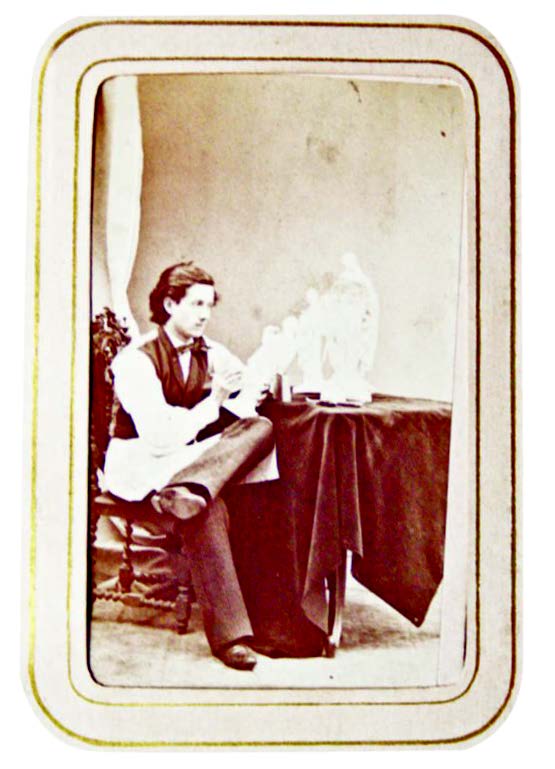

“This one or none”

She gathered all her courage and rang Stainer's doorbell. A tall, friendly young man opened the door. Anna stammered something about the letter and crept back down the stairs. But one thing was clear: "Now my destiny has come to me. I felt it with horror, this or nothing, it cried inside me." What impressed Anna so much about Engelbert Stainer was that the son of a sculptor born in Pfunds learned the shoemaker's trade, which he had little interest in. Until he took over a business that sold plaster figures. Stainer taught himself plaster molding with a lot of effort. And that was precisely what Anna Knittel found so inspiring about the man.

Engelbert Stainer, Anna Knittel's beloved and revered husband with plaster figures.

The two became engaged in 1867. During a visit to Elbigenalp, she introduced him to her parents and relatives. However, when Engelbert confessed that a former girlfriend was expecting his illegitimate child, she accepted this, but for her parents, this was the reason for a long estrangement. They forbade her to have any contact with him and broke off all contact with her. Her response: she would rather remain in poverty at Engelbert's side than leave him. This was a highly courageous decision at the time, revealing the fundamental character of this remarkable woman: she wanted to determine her own life and refused to be dictated to by others.

“No, Anna won't kneel down.”

Since the wedding was to take place in the same year, 1867, she traveled to Lechtal once again. At first, her father forbade her from entering the house and punished Anna with silence. "If I wanted to enter the house, I had to kneel at the front door and beg—me, kneel?" she recalls in her autobiography. "No, Anna will not kneel." After much persuasion, her father finally agreed, and the wedding took place on October 14, 1867, in the parish church of Elbigenalp. The honeymoon took them via Reutte to Hohenschwangau and from there to Munich. "But I wasn't happy in Munich anymore, I was fed up with it. He also longed to go home, so it wasn't even eight days. "This is how Steub's story about emptying an eagle's nest first appeared in 1863 in serial form in" Wolf's Illustrirter Rundschau, "published in Leipzig.2) Even back then, the magazine specialized in" adventure, criminal cases, and all kinds of remarkable events." Steub also admitted that he described the Lech Valley in his works "3 Summers in Tyrol" and "Tyrolean Miscellany" to give space to a story about "the remarkable feat performed by a girl from the Lech Valley that summer." In other words, Falger and his student Anna were the starting point for the Lech Valley's entry into the media spotlight of the time. I took the text of Anna Knittel's account of her courageous deed from Steub's "Tirolische Miscellen." It can be downloaded as a PDF file.

In her painting “Kirchgang in Elbigenalp” (Churchgoers in Elbigenalp), Anna Stainer-Knittel immortalizes the church where she was married and women in the beautiful but expensive traditional costumes of the Lech Valley.

On July 29, 1868, their first child, little Karl, was born. They moved into a new apartment in the Duregger House in Wilten, with an adjoining shop. “Two people couldn't stand next to each other in the apartment,” she recalls. “And yet we were more than satisfied, because the shop was spacious and gradually filled up.”

Anna Stainer-Knittel with short hair around 1865 © from: Nina Stainer – Anna Stainer-Knittel, painter..jpg

A photograph of Anna Stainer-Knittel from this period has been preserved, showing her with short hair. This was considered scandalous at the time, but it was simply a matter of course for Anna. In Innsbruck, Anna Stainer-Knittel could live the free life she had always dreamed of with her beloved husband. Looking back from today's perspective, this gifted artist was undoubtedly one of the first women in Tyrol to rebel against the oppressive male domination of the time successfully. No one could tell her what to do.

The quotations from Anna Stainer-Knittel's memoirs are taken from the very interesting work “Anna Stainer-Knittel, Malerin” (Anna Stainer-Knittel, Painter), published in 2015 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of her death by Nina Stainer, her great-granddaughter, by Wagner University Press in Innsbruck.

Literatur

Anna Stainer-Knittel Malerin

from Nina Stainer

The most comprehensive work on the life of Anna Stainer-Knittel is available as a book and e-book.

from Nina Stainer

The most comprehensive work on the life of Anna Stainer-Knittel is available as a book and e-book.

Autor

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler