Why did young Anna Knittel abseil down to the eagle’s nest twice?

Courageous actions were the reason why the young girl Anna Knittel suddenly became famous as the “Geierwally”. However, hardly anyone discusses the background that motivated the girl to take such a courageous action.

So why did “Nanno” – as Anna was known in the village – lower herself into the eagle's nest twice to remove the young birds, sometimes referred to as vultures in Tyrol, from the eagle's nest? This is a question that may concern many animal lovers today. And above all: where were the usually eloquent and powerful young lads, whose courage is normally boundless?

Mountain farming families fought for survival back then

Let's transport ourselves to Tyrol in the mid-19th century. Mountain farming families faced numerous overwhelming problems. Mountain farming was geared towards self-sufficiency. Even small “crop failures” could be fatal.

Market production – i.e., the sale of food – was really only possible for large farms. Additionally, the weather deteriorated significantly at that time, with cold spells beginning to set in. Potato blight devastated crops for several years in a row, resulting in widespread famines. The most famous was in Ireland, which forced hundreds of thousands of Irish people to emigrate. In Tyrol, the “Schwabenkinder” (Swabian children) were a reflection of this incredible emergency. (To save food, children were sent to Swabia to work in sometimes undignified conditions. But the family had one less mouth to feed, and the children usually earned a little money.)

The firm glacier maxima around 1820 and in the 1850s show that particularly wet and cool climatic conditions prevailed, which also affected agricultural land. The accumulation of crop failures led to the last great famine of the Vormärz period from 1846/47 onwards, which also severely affected Tyrol. Many families were no longer able to provide themselves with basic foodstuffs, and disease and malnutrition spread.

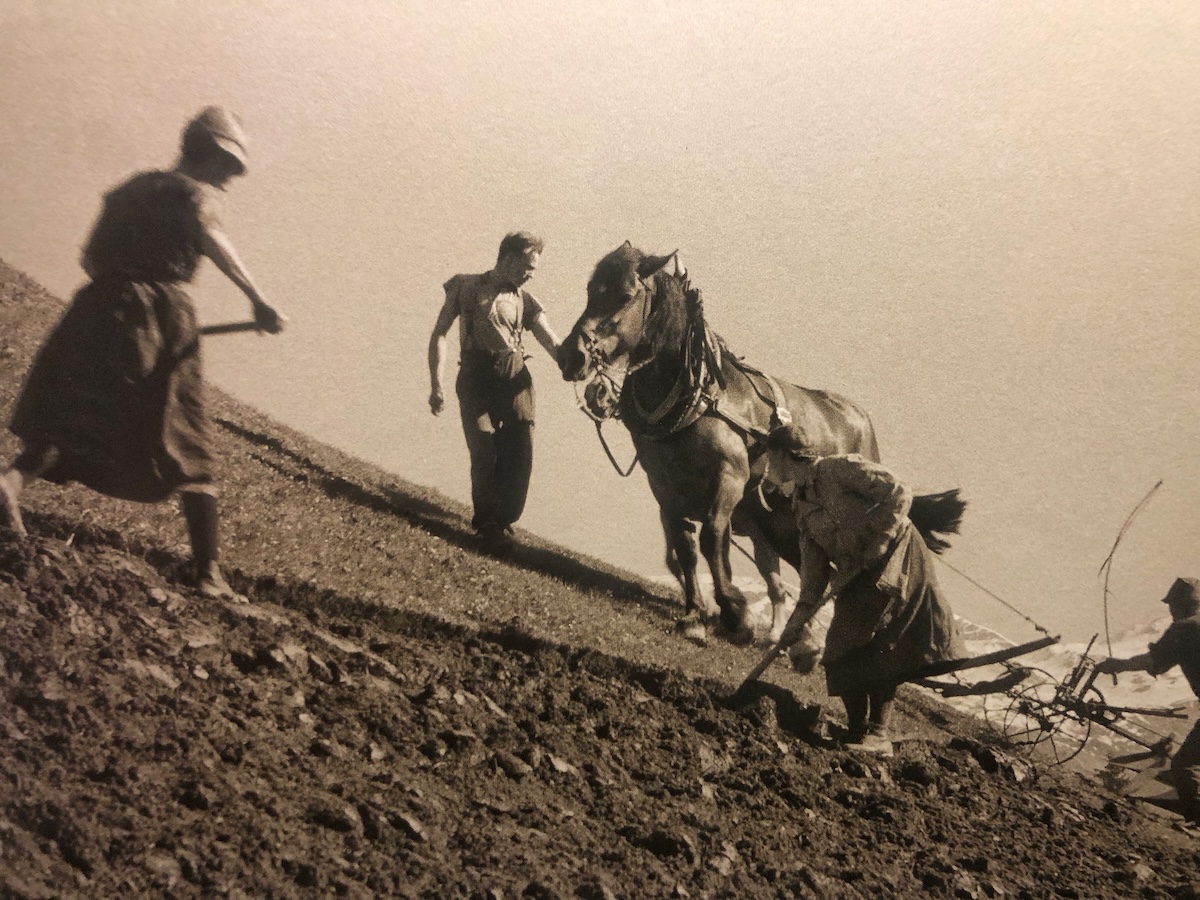

Image 1: Planting a potato field in front of the Oberkofl farm. ©Erika Hubatschek. From Das alte Tux (Old Tux); Image 2: Planting a potato field in front of the Oberkofl farm. ©Erika Hubatschek. From Das alte Tux (Old Tux)

Enormous efforts to earn a little money

Ludwig Steub describes the incredible efforts that mountain farming families made at that time to earn a little money in his travelogue from 1871: ‘Three Summers in Tyrol’. He recounts an incident that occurred while crossing the Tuxer Joch, when he met some people coming from Schmirn.

"On the pass, we met three Duxer (Tuxer), a man and two women, who were carrying butter to Steinach in their Krachsen (Kraxen). There is a large trade in butter from the Duxertal valley, and the inhabitants of both sexes carry more than three hundredweight over the passes to Innsbruck or to the towns on the Brenner road." (3 Summers in Tyrol, pp. 177, 178)

Not only did the three have to cover around 33 km to reach Steinach, but they also had to climb 1,000 metres in altitude. It was more than 50 km to Innsbruck. All this with probably 10-20 kg of butter on their backs.

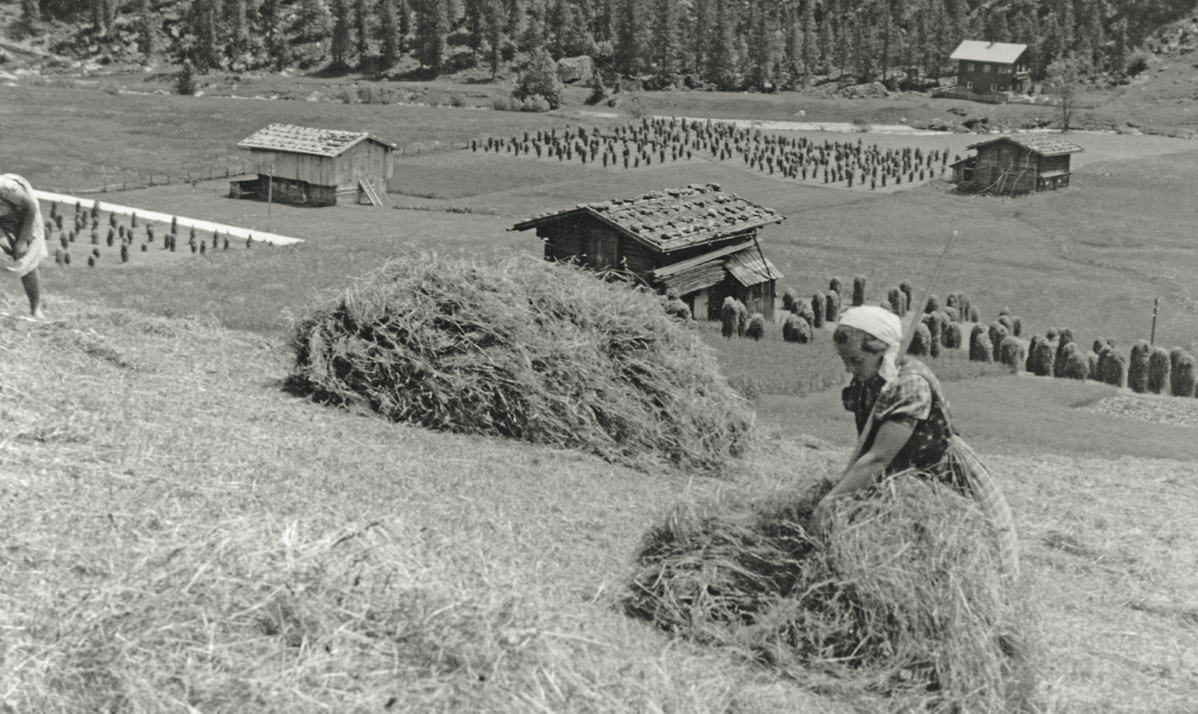

Image: Women haymaking. ©Erika Hubatschek

Predators were hunted

As early as 1727, Josef Knitel from Holzgau had established a trading post in the Netherlands because “Fortuna was generous” there. One of the many wholesale companies founded by three Lechtalers in Amsterdam gained considerable fame. It was described as “the most distinguished trading post” and made its partners fabulously wealthy. Lechtal traders were even active in America.

As Anton Falger, the “father of the Lechtal”, later explained in his description of the valley, there were already over 300 Lechtal traders abroad in 1799. Just imagine that! They traded throughout Europe, not only in cloth, bedding, bed feathers, jewelry, and haberdashery, but also in yarns, horses, violins, incense, linseed, brass, and ironware. In fact, they traded in anything that promised to turn a profit.

As Anton Falger, the “father of the Lechtal”, later explained in his description of the valley, there were already over 300 Lechtal traders abroad in 1799. Just imagine that! They traded throughout Europe, not only in cloth, bedding, bed feathers, jewelry, and haberdashery, but also in yarns, horses, violins, incense, linseed, brass, and ironware. In fact, they traded in anything that promised to turn a profit.

Successful merchants who returned to the Lech Valley with lots of money

In the struggle for their daily bread, predators were considered the sworn enemies of mountain farmers and were exterminated. Bears and wolves, for example. Eagles were also targeted. They were either shot or their young were taken from their nests. They threatened young animals on the alpine pastures, which at that time could mean hunger and hardship in winter for many families. So when eagles had young, it was time for a fight.

Images: Golden eagle from image database

Lambs as eagle prey

It makes sense: young birds are always hungry, so plenty of food has to be flown to the nest. This usually comes from prey that the eagles hunt among the wild animals. However, if the nest is located on a steep rock face very close to an alpine pasture, no pair of eagles will bother to chase nimble marmots, young chamois, or fawns. ‘Why wander far away when good things are so close’ is also the motto for the proud eagles. And the young lambs taste just as good.

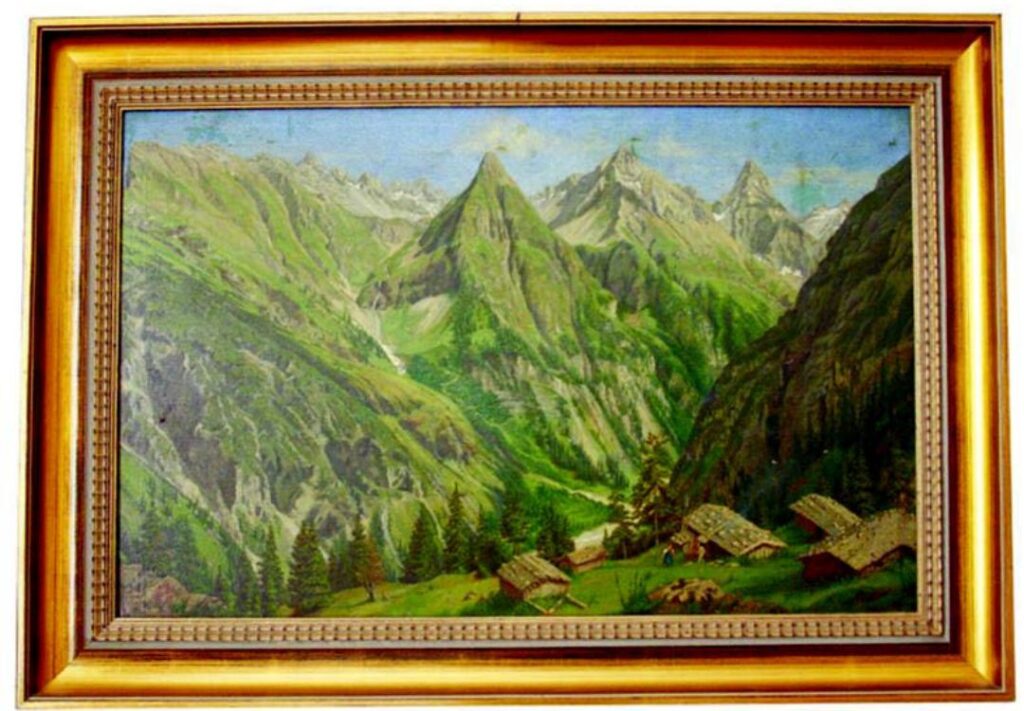

Saxerwand, painted by Anna Stainer-Knittel

The Saxerwand, down which young Anna abseiled, was an ideal nesting place for eagles. Directly in front of the wall lies the Saxeralm, where animals from Elbigenalp are summered. As early as 1858, Anna's father, Joseph Anton Knittel, a gunsmith, farmer, enthusiastic mountaineer, and hunter, had observed a pair of golden eagles with twigs in their beaks for the first time in the nearby Alberschonertal valley.

All attempts by “Loise”, as Anna's father was known in the village, to shoot the eagles using a rear sight and front sight had failed. So the young lads of the town had to show their mettle and abseil one of their own down to the eagle's nest. The operation almost ended in disaster: the rope got caught in a crevice, and the lad dangled for hours over the yawning abyss. Since he could no longer be pulled up, the rope was tied down, and messengers were sent to the valley to fetch the bell ropes from Elbingenalp. This allowed him to be rescued, but the lads' courage was gone. Not a single lad could be found who was willing to volunteer as an eagle hunter and make a new attempt to remove the nest.

Then, 17-year-old Anna, known as “Nanno,” said she was “the man for the job.” The next day, she abseiled down and took the young bird from the nest, which her father had, as always, placed in a shed in the attic to be fed up, so that it could later be sold to a menagerie or falconer. The birds became so tame that he only had to call ‘Mandl, come here’ and they would sit on his arm.

When Anna's father observed eagles building a nest again in 1863, as he had done five years earlier, he tried for 18 hours (!) to shoot the eagle. However, he failed several times. So he raised the alarm in the village.

The young lads, who should have been capable of such a feat, were, however, “cured” of abseiling into the eagle's nest on the Sachserwand. No one could be found who was willing to abseil down. So Anna set off for the wall with a master marksman, her brother Honnus, and a few other men. It was precisely this adventure that was to make Anna world famous.

She recounted her second eagle adventure at the request of the Bavarian writer Ludwig Steub, who published the text under the title ‘Die Lechthalerin’ or ‘Das Annele im Adlerhorst’ in the Leipziger Illustrierte and in the Tiroler Miscellen.

Author

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler

Erika Hubatschek's photographs offer a final glimpse into a time when mountain farming families lived solely to survive. The books are available from Hubatschek Publishing: https://www.edition-hubatschek.at/edition-hubatschek/publikationen/