A brilliant mind as Anna Knittel’s mentor

In the second installment of my blog on the remake of “Geierwally,” I would like to introduce the mentor who launched Anna Knittel's painting career. His name was Anton Falger. He motivated the young woman to write down her experiences during her descent into the Adlerhorst in the Madautal valley. This brilliant mind thus indirectly (and certainly unintentionally) ensured that Anna Knittel became world-famous as “Geierwally.”

At the beginning of young Anna Knittel's artistic career stood a brilliant man whose name is still spoken with the utmost respect in the Lech Valley today: Anton Falger. The lithographer, copperplate engraver, artist, art collector, geologist, and meticulous archivist of the valley is revered as the "father of the Lech Valley." Thanks to his knowledge and skill, he immediately recognized the talent of the young Anna Knittel and promoted her extensively. In the mid-19th century, this great Lech Valley native ran a painting school in Elbigenalp. Suppose you are now thinking of the woodcarving school in Elbigenalp. In that case, you are right: Falger was at the cradle of this important Tyrolean art school. Without him, one of our country's most beautiful and remarkable small museums would not exist: the 'Wunderkammer' in Elbigenalp.

Anton Falger: a man of the world

The talent of Anton Falger, born on February 9, 1791, into a family of bakers in Elbigenalp, became apparent early in his life. At 15, the gifted draftsman began an apprenticeship as a church painter. From 1808, he trained at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. In 1809/10, he joined the Bavarian Landsturm, which famously fought alongside Napoleon. “God preserve us from revolution and civil war, the most miserable of all miseries,” he confided in his diary.

Falger was directly involved in the fighting during the Napoleonic Wars on the side of Bavaria. He drew a whole series of battle scenes. This picture shows the fighting on the Inn Bridge in Innsbruck on April 12, 1809, and is based on a model by Placidus Altmutter. ©Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

The battles on Mount Isel also preoccupied the painter Anton Falger. Here is the Battle of Mount Isel on August 13, 1809, again based on a model by Placidus Altmutter. ©Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

From 1810, he was an engraver in the Bavarian Tax Cadastre Commission, which produced maps. Between 1813 and 1815, he participated in the Napoleonic Wars as a non-commissioned officer, fighting in battles that took him as far as Paris, which he later captured in drawings. On April 1, 1814, he even marched into Paris with Bavarian troops, “one of the most remarkable days of my life,” as Falger said in his memoirs.

The Battle of Hanau also inspired Falger as an artist. Here is a depiction of this battle. ©Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

Goethe praises Anton Falger

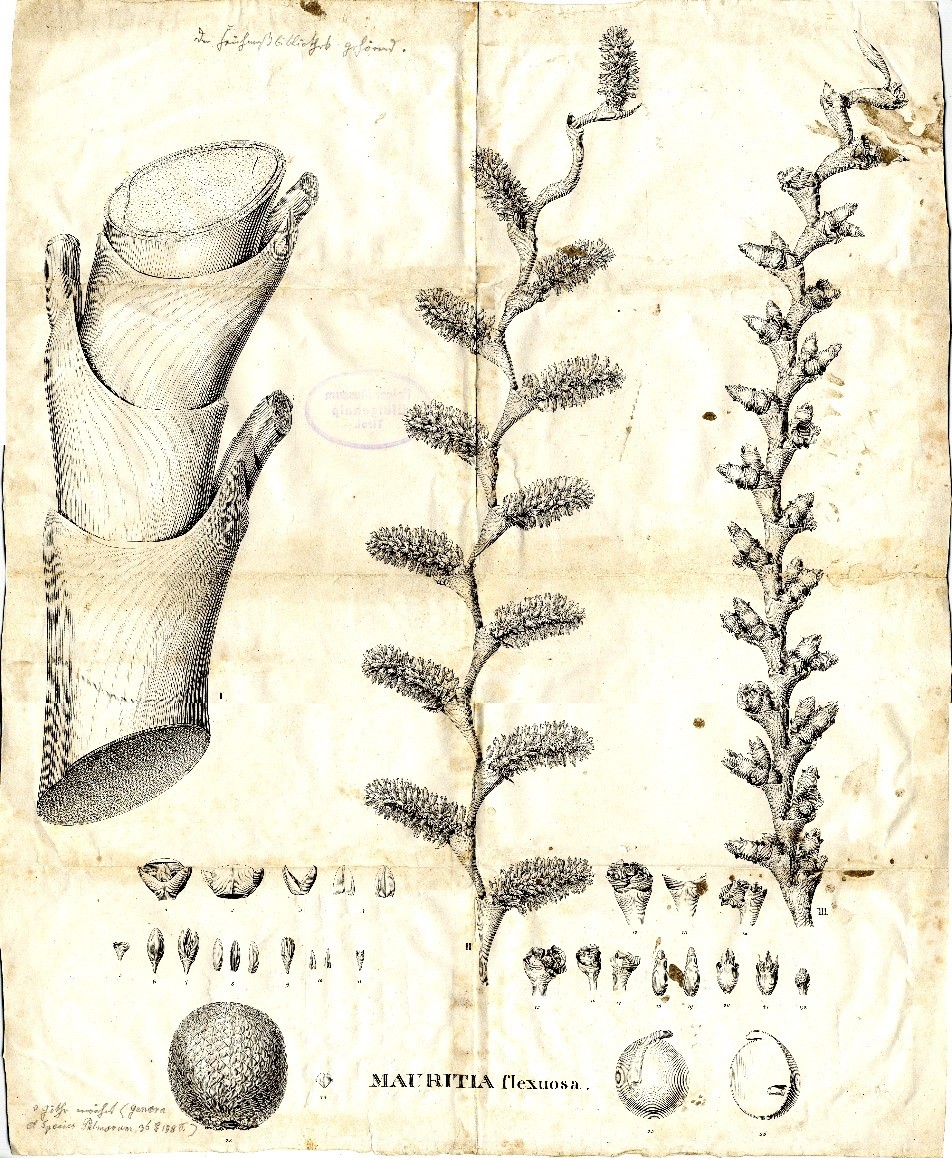

After Napoleon's defeat, he returned to Munich and became part of the circle of friends surrounding Alois Senefelder, the inventor of lithography, which was revolutionary then. Falger was undoubtedly one of the first true 'masters' in using lithography. This fact helped him gain some fame in Germany at the time. He was lured to Weimar, presumably with generous salary offers, to set up a lithography workshop there. There, he also met Privy Councilor Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe held the work of the great master from the Lech Valley in high esteem. He even immortalized him in his complete works. Falger describes the print shown below in his memoirs as follows: "This is a sheet from the great work Genera et Species Palmarum v. Hofrath v. Martinus, for which I engraved many sheets in stone in Munich, and this great work by the poet Goethe was so well received in Weimar that he mentioned me in his work in the 36th volume, page 185 (in the 46-volume edition) and also in the 32nd volume, which was published as a 32-volume edition, page 106."

A workaholic of the purest kind

In 1821, Falger returned to Munich and worked there as a lithographer. In 1831, he decided to return to his valley. From then on, he lived and worked in Elbigenalp. I wondered how he managed to retire at the age of 40. After all, no pension system or life insurance could be paid out at that time. But of course, Falger came from a middle-class family and earned a decent living as a lithographer. A diary entry provides some clues: during his time in Weimar alone, from March 5, 1819, to October 12, 1821, i.e., in two and a half years, he earned “3,660 fl (gulden) and spent approximately 320 fl.” His 10 years as a lithographer in Munich were probably similarly successful financially. By comparison, a large house in the Lech Valley would cost around 1,600 guilders. So Falger had considerable financial resources at his disposal.

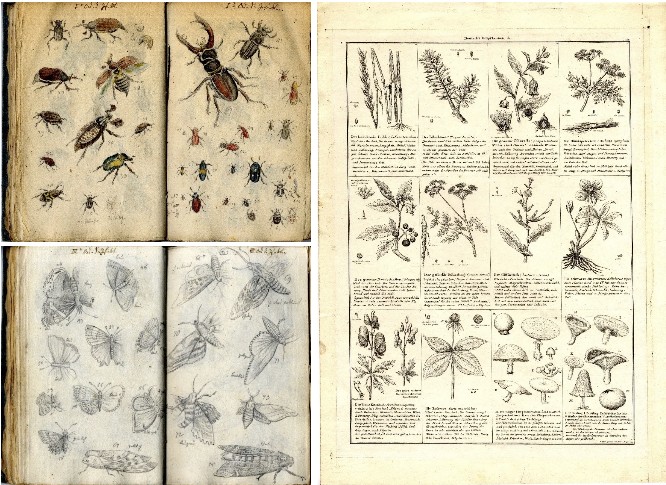

Anton Falger mapped, collected, drew, and interpreted virtually everything that his Lech Valley had to offer. Here, for example, are sketches of insects that he captured in minute detail. He also worked to educate the public about the poisonous plants of his homeland, which he recorded on an information poster and, of course, reproduced using lithography. This is just a fraction of what he produced in graphic form. ©Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

In Elbigenalp, he ran a drawing school, the precursor to the local technical college for arts and crafts and design. He devoted himself to every conceivable field of study. It is incredible how much work Falger accomplished in the Lech Valley. We owe a debt of gratitude to the late Mag. Reinhard Schlichtherle for compiling this intellectual giant's enormous collection of notes, lithographs, paintings, and nature studies in a publication by the Wunderkammer Elbigenalp. “Notizen über Lechthal” (Notes on Lechthal) gives an impression of what Falger achieved for the valley as a scholar, artist, and collector. The book is available for purchase at the Wunderkammer in Elbigenalp.

In 1861, the highly talented Anna Knittel produced this lithograph of her revered teacher Anton Falger.

In addition to creating a series of images depicting the dance of death, conducting research and producing illustrations on local flora and fauna, the geology of the Lech Valley, the basic conditions in his hometown, and descriptions of the destructive paths of avalanches and mudslides, he devoted himself primarily to nurturing young artists in Elbigenalp at his drawing school. And so it was he who discovered the talent of the young Anna Knittel.

Anna Knittel at Falger's drawing school

“Our father had shown our drawings to Mr. Falger, who thought highly of my talent and persuaded our father to let me attend his drawing school on holidays, as he gave free lessons to gifted boys every winter,” Anna Knittel describes the beginnings of her artistic career. At first, she thought her sister ‘Honnele’ was more talented than she was.

His marriage to Theres Seep was the real reason why Anton Falger retired to Elbigenalp. This lithograph from 1861 was also created by Anna Knittel. ©Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

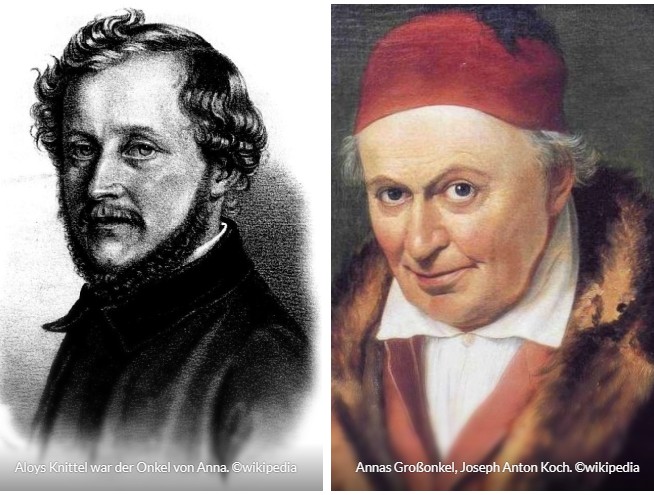

Why did a farmer and gunsmith from the Lech Valley encourage his daughter's artistic ambitions? The answer is provided by Nina Stainer, one of Anna's descendants, in her work “Anna Stainer-Knittel, Painter”: "Quite simply, art and craftsmanship had been firmly rooted in the Knittel family for several generations. One of Anna's great-uncles was the renowned landscape painter Joseph Anton Koch, and her uncle Josef Aloys Knittel was a sculptor in Freiburg."

Training in Munich

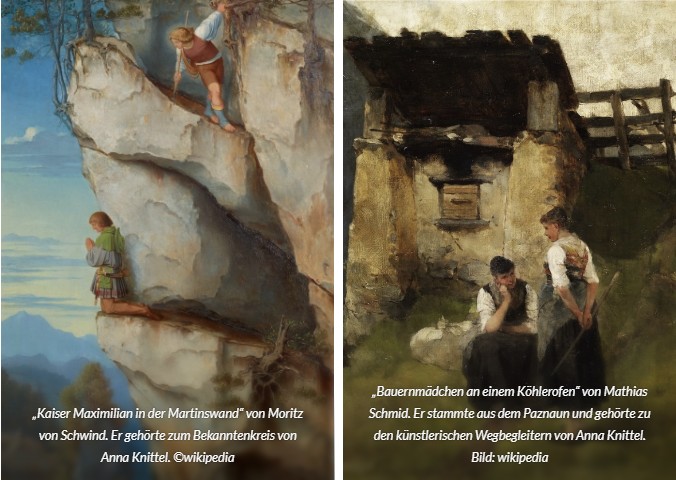

Anton Falger was so impressed by Anna's talent that he got her a place at a preparatory school for the Munich Art Academy and even financed her education. At that time, women were not allowed to enroll at the art academy. She studied under renowned teachers and got to know famous figures such as Moritz von Schwind, Joseph Anton Schwarzmann, and Mathias Schmid. At the end of 1861, she returned to Elbigenalp, hoping to earn a living in her specialty, portrait painting.

When vultures and eagles were still sworn enemies of alpine farmers

However, 1862 was to be Anna Knittel's year. In addition to her housework and fieldwork, she devoted herself to her studies with a single goal: to move to Innsbruck and establish herself professionally there. When her father, a gunsmith and an enthusiastic hunter, discovered an eagle's nest in the Saxergwänd for the second time, into which the eagles flew to build their nest, all hell broke loose. The lambs in the nearby Saxeralm were in danger, so, just like five years earlier, the eaglet had to be rescued from the nest. This was especially important because neither Anna's father nor her brother could "shoot" the eagle in the nest, as they had done five years before Anna's first rescue. This time, however, a saga began that would soon develop into a modern myth. It praises the courage and determination of the young Anna Knittel, but at the same time, it distracts from her actual skills and her true calling.

Die Saxeralm im Madautal. ©Lechtal Tourismus

But how did a local event become a kind of heroic saga, in which a woman played the leading role? One of Germany's great "travel writers," Ludwig Steub, laid the foundations for this. He traveled through Tyrol on foot for several years to describe the mountainous region. During his travels, he visited Anton Falger, who was highly respected throughout the Lech Valley. Steub had probably read in a newspaper article that a young girl had shown extraordinary courage by abseiling into an eagle's nest. He asked Anton Falger to ask his student to write an account of her 'feat' in her own words, which Anna Knittel did. The rest is a sensational story I will tell in my next blog.

Author

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler