‘From the confines of the valleys to the vastness of thought.’

As a young woman from the wild Lech Valley, Anna Knittel dared to do something in the 19th century that few women dared to do at the time: she wanted to become a painter. And this in a world that regarded art as a “primordially male” privilege.

Her path to becoming an artist began in modest circumstances. Her strong, unyielding will and the support of her mentor Anton Falger made her one of the most important female figures in Tyrol. Almost 200 years ago, she was already determined to take control of her own fate. Her life story is not only an art chapter, but also about a woman's struggle against social barriers and conventions.

Departure from the Lech Valley

Anna Knittel's talent for painting became apparent at an early age. Her father, a proud hunter and gunsmith, recognised her gift and entrusted her to the care of the well-known artist and lithographer Anton Falger. Falger, himself a versatile researcher, illustrator, and teacher, was enthusiastic and took her under his wing. He encouraged her to continue her education and eventually paved the way for her to attend the preparatory school of the Royal Academy of Arts in Munich, where he helped her gain admission–a notable achievement, as women were not yet officially allowed to attend.

Image: Anton Falger drawn by Anna Knittel

The rocky road to training

In the autumn of 1859, Anna and her father, financially supported by Falger, set off on foot for Munich – a journey of almost 200 kilometres. Once there, she encountered the brutal reality of the male-dominated art world: the Academy of Fine Arts did not accept women. Instead, she was only allowed to attend the so-called ‘pre-school’ – a preparatory course that permitted women to draw on a modest scale, but did not offer academic titles or a complete education.

Anna lived in extremely modest circumstances. She lived in a sparse boarding school, often struggling with hunger and loneliness. In letters, she described how she could barely afford her painting supplies, how she was homesick for the mountains, and yet at the same time, she experienced the city as a place of freedom. Every sheet of paper was precious to her – so much so that she ‘almost regarded the chalk dust cloth as bread,’ as she later wrote.

But she did not let herself be discouraged: instead of giving up, she sought out teachers outside the academy who would give her private lessons. One of her first mentors in Munich was the painter Josef Muhr, from whom she learned portraiture and the art of copying. It was a laborious yet profound education: Muhr taught her precision of vision, the modeling of faces, and respect for light.

Living and studying in Munich

In Munich, Anna Knittel met several notable artists and gained valuable insights into the art scene of the time. Particularly influential was her exchange with Mathias Schmid, a Tyrolean genre painter who trained her stylistic sensibility and deepened her connection to her homeland. Equally significant was her acquaintance with the renowned Romantic artist Moritz von Schwind, who influenced her with his poetic visual language.

A key moment was her visit to the studio of the legendary Karl von Piloty, the leading history painter of the time. His monumental scenes and dramatic figure studies filled Anna with both awe and inspiration. In her notes, she wrote how small she felt in the presence of such artistic greatness – and yet how much this moment spurred her on to develop her own style.

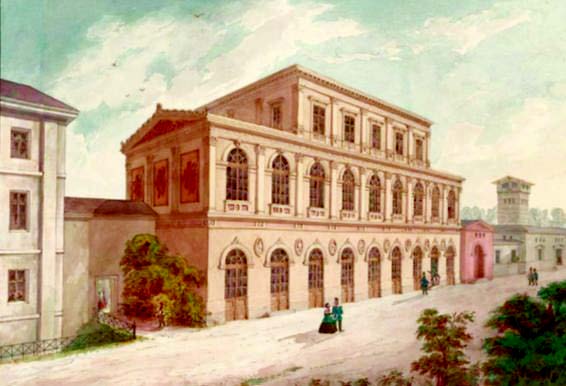

Image: Blick auf München vom Maximilianeumaus, Lithographie, vor 1892

Image: View of the club building at Munich's Hofgarten, far left: passageway to the arcades, Eduard Riedel 1866

The images were taken from Nina Stainer's work ‘Anna Stainer-Knittel Malerin’ (Anna Stainer-Knittel, Painter). The most comprehensive work on Anna's life.

Social barriers

For a woman of her time, painting was not only an artistic risk, but also a moral one. Drawing nude models was considered indecent, and visiting the studios of strange men was considered improper. Anna Knittel deliberately broke these taboos: she ventured into female nude studies, studied anatomy, and repeatedly attempted to push the boundaries of what was considered ‘appropriate’ for a woman.

Image: Anna Stainer-Knittel with short haircut

Her fellow students – few in number and often isolated women – formed a small, supportive community. But in public, their contribution remained invisible. Art critics often overlooked her work because she was a woman. Nevertheless, her diligence and talent earned her growing recognition: her portraits, especially her ‘Self-Portrait in Lechtal Costume’ from 1863, even impressed the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum, which purchased the work – an extraordinary honour for a female artist of that time.

Encounters and lasting impressions

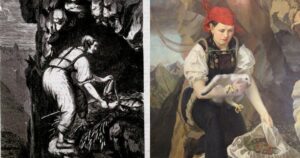

Her time in Munich had changed Anna Knittel forever. She had learned from the best – Piloty, Schwind, Schmid – and at the same time experienced how little space was given to women in art. This experience turned her into a fighter for education and self-determination. Her life was exemplary for many women of the 19th century who, unlike those born into salons, had to work their way into the art world. Her name seemed to merge with the deed that had made her famous as “Geierwally”: a woman who, as a woman, had always fought for freedom and self-determination. And in doing so, had fought her way into art history.

Image: Mathias Schmid, Farm girl at a charcoal kiln

Her time in Munich had changed Anna Knittel forever. She had learned from the best – Piloty, Schwind, Schmid – and at the same time experienced how little space was given to women in art. This experience turned her into a fighter for education and self-determination. Her life was exemplary for many women of the 19th century who, unlike those born into salons, had to work their way into the art world. Her name seemed to merge with the deed that had made her famous as “Geierwally”: a woman who, as a woman, had always fought for freedom and self-determination. And who had thus fought her way into art history.

She herself later wrote that the journey to Munich had led her ‘from the confines of the valleys to the vastness of thought’ – a sentence that sums up her life's work.

Author

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler

Recommended reading:

Freelance journalist and author Alexandra Keller has written a wonderful piece about Anna Stainer-Knittel, which I would like to recommend to readers: https://www.lebensraum.tirol/geierwally-superstar/