Geierwally and summer freshness: The beginnings of Alpine tourism

Two events collided in the middle of the 19th century: the courageous deed of a girl from the Lech Valley and the introduction of a term into the German language that was to become synonymous with early alpine tourism. Both can be traced back to a single travel writer who began exploring Tyrol on foot in the first half of the 19th century to describe the country and its people. His name was Ludwig Steub.

The origin of the myth of “Geierwally” would not have been possible without the chance encounter of two great men: Anton Falger, the brilliant researcher, artist, archivist, and art collector from the Lech Valley, told the Bavarian lawyer and writer Ludwig Steub the incredible story that celebrates the courage of a young girl. (We described Falger in the blog no. 2) Ten years later, the romantic exploitation of the story in the novel “Die Geierwally” by a Bavarian noblewoman came when the Alps were losing their terror. It was a turning point, namely the beginning of the tourist development of the Alps, which continues to this day and is destroying parts of the mountain range in the long term.

Ludwig Steub (left) and Anton Falger: two true “discoverers” of Tyrol. Steub was a writer, Falger a fantastic lithographer, keen observer of nature, archivist, and art collector. Images: Wikipedia, Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

The Alps were once a ‘place of horror’, a ‘locus horribiles’.

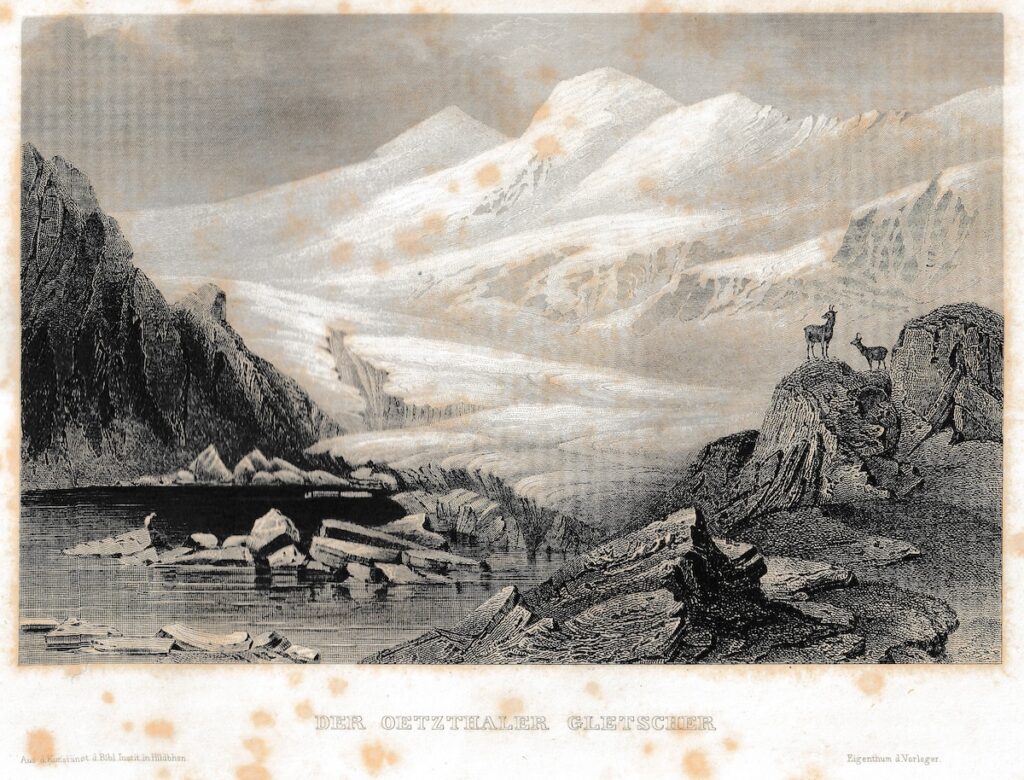

It took great courage when writers in the mid-19th century began venturing on foot into the remote Alpine valleys. The rugged mountains, the menacingly glistening glaciers, and the raging rivers that forced their way through narrow gorges were considered dangerous, even hostile to life. Reports of glacial lake outbursts, avalanches, and mudslides with devastating consequences for the Alpine valleys sent cold shivers down the spines of city dwellers time and again.

"In the past, ‘the mountains’ did not exist. They were merely obstacles that travelers had to overcome, terrifying seas of rocks, terrifying precipices. In short, people ignored this cruel natural environment inhabited by a shy, frugal population. It was—as often described in literature—a veritable locus horribilis. No one ventured into the area unless they had to." 1) Renate Papst-Gerblinger

The Gurgler Eissee lake with the Gurgler Ferner glacier around 1860, at the time when Steub was traveling through Tyrol. From: Wikipedia, Meyers Universum Volume 21 18.

Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber made Tyrol accessible for the first time

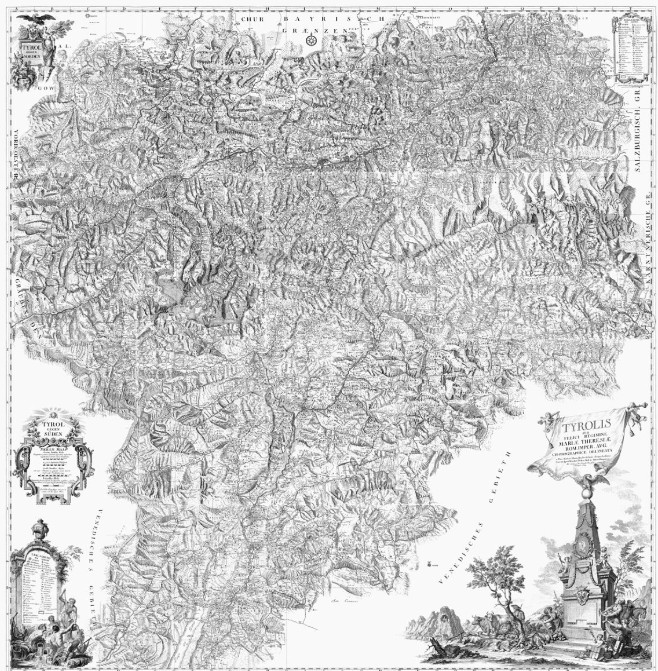

The two Tyrolean "farmer geographers," the brilliant Peter Anich and his equally brilliant student Blasius Hueber, mapped the province of Tyrol for the first time between 1760 and 1774 in a sensationally accurate map. In doing so, they also paved the way for exploring Tyrol. In the wake of this, it was mainly German writers such as Karl Baedeker, Heinrich Noë, and Ludwig Steub who threw themselves into the task with equal enthusiasm. They all began exploring Tyrol in the first half of the 19th century and explored it virtually "far and wide." I consider Ludwig Steub's "Three Summers in Tyrol" and "Tyrolean Miscellany" to be the descriptions of Tyrol that presented the country in a comprehensive and attractive light, but above all as appealing to travelers and tourists. (Both of Steub's works are available at the bottom of this page as PDF files for interested readers to download. I want to thank the University Library of Innsbruck for their permission. For me, Steub is highly recommended reading for all Tyroleans.)

An incredible achievement by Peter Anich and his student Blasius Hueber: the map of Tyrol. It was one of the most significant cartographic achievements of the 18th century. Image: Wikipedia

Steub coined the term “summer retreat”

Steub did not just describe the landscapes, mountains, rivers, villages, roads, and churches. He was just as interested in the people who lived and worked in the valleys. He also recounts many amusing episodes related to the belief in saints that is still inherent in the Tyrolean people today. The inclusion of the inhabitants of Tyrol results in a complete and well-rounded picture of the realities of our country at that time. On this occasion, he also coined the term, aptly defining the first century of tourism in Tyrol: the "Sommerfrische" (summer retreat). (And because I am so taken with Steub, I will share some "gems" from his descriptions in my next blog. Don't forget: if you subscribe to the blog for free, you will be the first to know when a new blog is online.)

Steub's visit to Anton Falger: the birth of the Geierwally myth

His explorations of the Lech Valley – Steub naturally traveled on foot – also took him to Elbigenalp. There, he sought out Anton Falger, who had already achieved some fame at that time. When he first heard the story of the courageous Anna Knittel, presumably from Falger, Steub immediately recognized its journalistic significance. Since Anna was a student at Falger's drawing school, he asked Falger to ask her to tell the story in her own words, which Anna did. Steub edited the text, and "Im Adlerhorst" (In the Eagle's Nest) fitted perfectly into the emerging "magazine culture" that had spread throughout Germany and is still enjoying a revival today.

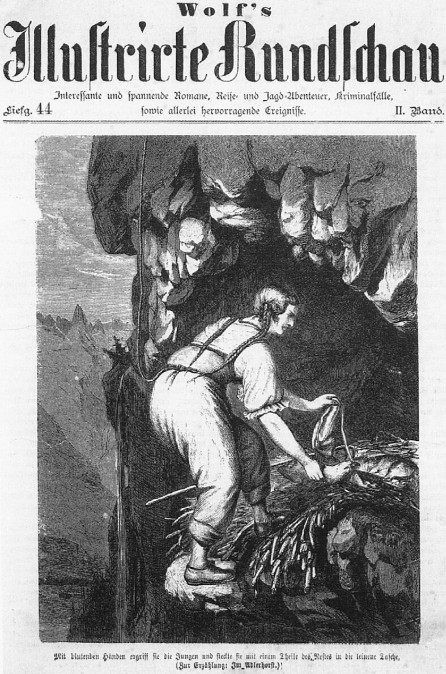

Thus, in 1863, Steub's story about the ransacking of an eagle's nest appeared for the first time in serial form in "Wolf's Illustrirter Rundschau," which was published in Leipzig.2) Even back then, the magazine specialized in "adventures, criminal cases, and all kinds of remarkable events." Steub also admitted that he described the Lech Valley in his works "3 Sommer in Tirol" (Three Summers in Tyrol) and "Tyroler Miscellen" (Tyrolean Miscellany) to give space to "the remarkable feat performed by a girl from the Lech Valley that summer." In other words, Falger and his student Anna were the starting point for the Lech Valley's entry into the media spotlight of the time. I took the text of Anna Knittel's account of her courageous deed from Steub's "Tirolische Miscellen." It can be downloaded as a PDF file.

Anna is annoyed by a graphic in Wolf's Illustrated Review by one of her acquaintances, which shows her digging out the eagle's nest.

Anna Knittel strongly disagreed with one crucial detail of the publication: the graphic that served as the lead image for issue No. 1069 of the magazine. It shows Anna in the eagle's nest, packing the young eagle into a linen bag she brought. In her memoirs, she criticizes not so much the text as the illustration. Her acquaintance, the Tyrolean painter Matthias Schmid, created an illustration for the Illustrirte Rundschau showing her performing her daring deed. However, contemporaries met the illustration with some derision, as the heroine turns her very ample backside toward the viewer. The voluminous depiction of the pants is based on Anna's description that she had pulled pants over her voluminous skirt for her mission at the eagle's nest.

Mathias Schmid, a good acquaintance of Anna Knittel, created the engraving that depicted her courageous act in Wolf's Illustrirte Rundschau. Anna herself “grumbled” about the depiction, as she had been mocked for the “broad rear end” Schmid had drawn. Anna decided to counter the lead image with a self-portrait. That was the way fact-checking was done back then.

Anna's anger culminates in the famous self-portrait in the eagle's nest.

But the fun ended when she was given an illustration with the following caption: “Schmid diligently paints farmers, monks, and even bailiffs, but the butt of the bold Miss Knittel was uncertain.” “I grumbled incessantly,” Anna Stainer-Knittel recalled in her memoirs. She then picked up a brush and painted herself to create a large-format picture of herself.

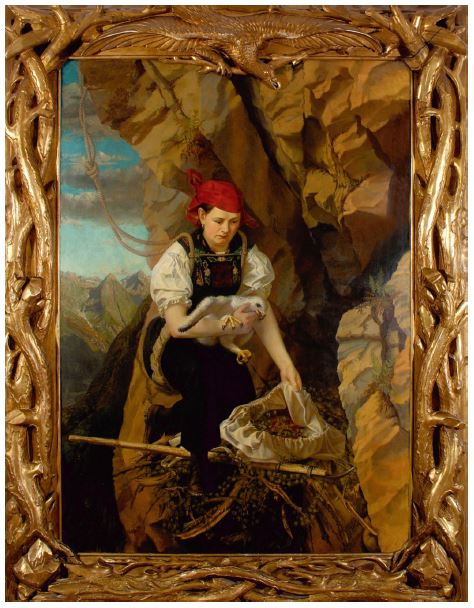

Anna Knittel's self-portrait of her descent into the eagle's nest and the rescue of the young eagle in a linen bag. You can also see the most essential tool used in this operation, a ‘Grieshaken’, which is usually used to fish wood out of the river. However, she needed it to push herself off the rock and pull herself into the eagle's nest.

In the novel, Anna becomes Walpurga and the eagle becomes a vulture.

However, the time was not yet ripe to turn Anna Knittel's courageous deed into an Alpine saga with a huge impact. This step was taken around 10 years later with the publication of Wilhelmine von Hillern's novel "Die Geierwally" (The Vulture Wally). The fact that the aristocratic author had turned Anna into Walpurga and an eagle into a vulture was of secondary importance. The rebellion of the main character, Wally, against her father, the sweeping descriptions of the "wild Alps," and the concessions of the time made the novel so appealing. If a comparison is permitted, it was the Alpine version of Shakespeare's comedy "The Taming of the Shrew" with a strong tendency toward drama. Anna's, or rather Wally's, courage in taking an eagle's nest from a steep rock face in the wild Alps made her deed so unique.

Wilhelmine von Hillern in an engraving by Adolf Neumann. The aristocratic writer probably cast herself in the role of “Geierwally” as she would have liked to see herself: rebellious. If contemporary sources are to be believed, she was very much under the thumb of her mother, who was a well-known actress. Image: Wikipedia

Was “Die Geierwally” a kind of plagiarism?

I am not alone in assuming that the novelist Wilhelmine von Hillern had read about the courageous deed in Wolf's Illustrirte Rundschau. At the time, the magazine described "interesting and exciting novels, travel and hunting adventures, criminal cases, and all kinds of outstanding events," i.e., material for potential novels. Wilhelmine von Hillern's work not only catered to city dwellers' longing for "natural life in the countryside and mountains." With her portrayal of the "rebellious" Wally, she also appealed to middle-class women's burgeoning emancipation efforts. In addition, her relationship with her biological mother was probably troubled. Von Hillern undoubtedly suffered from many of the conventions imposed on aristocratic ladies. In the novel, she fantasizes about resistance and daring, quasi on her behalf. Ultimately, however, she throws herself unconditionally into the arms of her fictional lover. This is actually in the style of Shakespeare's comedy "The Taming of the Shrew."

Indeed, Anna Knittel did not enjoy her 'new role' as Geierwally. Whether Mrs. Hillern ever actually spoke to her remains unconfirmed. Rumor has it that she saw Anna Stainer-Knittel's self-portrait in the shop window of her husband, Engelbert Stainer, and subsequently wrote the novel. Anna did not mention this in her memoirs and barely described the episode. A brief reference in her memoirs to the two courageous deeds in Saxergwänd was a request that readers refer to her account of the events in Wolf's Illustrirte Rundschau. For her, this "alter ego" attributed to her was, in the truest sense of the word, unimportant. She did not see herself as an adventurer but as an artist.

In the next blog, I would like to introduce you to the province of Tyrol in the mid-19th century. Based on Ludwig Steub's descriptions, there are all kinds of funny and remarkable things to discover. The text is a journey back to when Alpine tourism began, Franz Senn founded the German-Austrian Alpine Association, and the first mountain guides began to accompany tourists to the mountain peaks, like the Klotz brothers of the Rofenhöfe above Vent.

Author

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler