The Lech Valley of young Anna Knittel

One would generally assume that the Tyrolean Lech Valley was one of those impoverished Alpine valleys in the 18th and 19th centuries where life was a constant struggle for survival. However, this valley was a remarkable exception, at least from the 18th century onwards.

There are astonishing reasons why the Lech Valley enjoyed a certain prosperity in the 19th century. In this blog series, I want to describe them, as well as the circumstances that turned Maria Anna Rosa Knittel, a girl from the Lech Valley, into the famous painter Anna Stainer-Knittel, who was long overshadowed by her alter ego, the legendary novel character "Geierwally." I want to point out that much of the data and facts in my blog series are taken from the "Lechtal Chronicle" by the legendary and brilliant lithographer, artist, local historian, and mentor of Anna Knittel, Anton Falger. The details of the activities of the Lechtal moneylenders, which will be discussed in this first blog, are taken from Martin Mennel's book "Die Lechtaler als Geldverleiher im Bregenzerwald" (The Lechtalers as moneylenders in the Bregenz Forest).

Anton Falger. The “father of the Lech Valley,” artist, lithographer, archivist, and mentor, depicted in 1861 by Anna Knittel. His meticulous records of the Lech Valley are essentially the cultural heritage of this unique part of Tyrol.

How bricklayers from the Lech Valley laid the foundations for the valley's prosperity

Bitter poverty marked the beginning of the minor economic miracle in the Lech Valley. It drove many men from the valley as early as the 17th century to work as bricklayers between April and November 11. In 1699, 644 men were working as bricklayers abroad, writes Anton Falger. The men found work in eastern Switzerland, Alsace, Germany, and as far afield as Holland. Iron-fisted saving enabled some of them to build up small reserves of money. Their wives ran the show at home, caring for the farm, raising the children, and developing various survival strategies. In the mid-18th century, many still had to send some of their children to Swabia in the summer to be fed there, as there was hardly any food at home. As late as 1830, around 5,000 so-called “Schwabenkinder” (Swabian children) emigrated from Tyrol and Vorarlberg to Swabia, where they often had to work for wealthy farmers under appalling conditions.

The heartbreaking fate of the “Schwabenkinder” (Swabian children) is also an expression of the hardship and poverty experienced by many farming families in the 19th century. The picture shows Schwabenkinder from Graubünden in 1907. Image: Wikipedia

Flax, linen, and bricklayers were the saviors of the Lech Valley.

In the Lech Valley, a plant appeared in the 18th century that seemed to lift an entire valley out of poverty: flax. Originally, flax was cultivated and processed in the Lech Valley to produce linen fabrics, mainly for personal use. Surpluses, mostly in the form of yarn, could be sold. Linen was hardly marketable in the valley itself, as people could not afford it. This is where the men who had once left home as bricklayers and acquired local and linguistic knowledge abroad came into play. Many of them put down their trowels and became traveling salespeople. Their immense advantage was that they knew the people, cities, and countries where the expensive linen yarn could be sold from personal experience.

Flax fibers are usually obtained in “tauröste”: the harvested flax plants are left lying in the field where the hard shell is decomposed by fungi and bacteria. The durable fibers remain.

More and more of these former bricklayers began selling flax. Since bundles of a certain length were called “Schneller,” these traders were called “Schnellerhändler.” They set off with their panniers and took snuff boxes and bells from Häselgehr with them. No distance was too far, and no pack was too heavy. They moved to the countries they knew from their work as bricklayers: eastern Switzerland and down the Rhine to the Netherlands. Some even ventured as far as England and America.

A Tyrolean carpet dealer in a contemporary depiction. This is how one might imagine the itinerant traders of the Lech Valley. Image: Tyrolean carpet dealer from Brand's Kaufruf, Vienna 1775.

Trade makes you rich

As early as 1727, Josef Knitel from Holzgau had established a trading post in the Netherlands because “Fortuna was generous” there. One of the many wholesale companies founded by three Lechtalers in Amsterdam became well-known and famous. It was described as “the most distinguished trading house” and made its partners extremely wealthy. Lechtal traders even became active in America.

Anton Falger, the “father of the Lech Valley,” later explained in his description that there were already over 300 Lech Valley traders abroad in 1799. Just imagine that! They traded in cloth, bedding, bed feathers, jewelry, haberdashery, horses, violins, incense, linseed, brass, and ironware throughout Europe. They traded in anything that promised a profit.

Successful traders who returned to the Lech Valley with lots of money

However, most of these men who had been successful abroad longed for their homeland. Many sold their companies and shops and returned to the Lech Valley, where they were now wealthy. This promptly led to a construction boom. The returnees had elegant stone houses built and plastered the exterior of their wooden houses. Lüftlmalerei became a visible expression of the immense wealth of many builders. Here are a few examples of houses in the “Lüftldorf Holzgau.”

Some also paid great attention to interior design. For example, a former silk merchant from Holzgau had a salon furnished with urban Biedermeier furniture. Even back then, people indulged in exquisite things.

Women ‘rushing by’ embodied wealth

It is hardly surprising that this new prosperity was also reflected in the women's magnificent clothing and jewelry. According to chronicler Anton Falger, the most incredible luxury was enjoyed by a certain Magdalena Lumperin. "It was said that she owned 64 dresses and more than a dozen pairs of shoes." When such rich women walked through Elbigenalp, people would say, "Here they come again..." because the heavy fabrics rustled as they walked.

In her painting “Kirchgang in Elbigenalp” (Churchgoers in Elbigenalp), Anna Stainer-Knittel immortalizes women in the beautiful but expensive traditional costumes of the Lech Valley.

Even the fairy-tale king Ludwig II was a guest at the Lechtaler

From 1867 onwards, wealthy residents of the Lech Valley could even afford to invite the Bavarian Queen Mother Marie of Bavaria, her sons King Ludwig II—the “fairytale king” with the castles—and Prince Otto, along with an entourage of 30 to 50 people, to Elbigenalp on several occasions and, of course, to provide them with food and drink. In 1873, the Queen Mother spent seven weeks in the Lech Valley. She enjoyed the generous hospitality of the Lechtal residents, who otherwise allowed themselves few luxuries.

Even the “Kini” enjoyed dining in the Lech Valley. He accepted invitations from wealthy Lech Valley merchants and spent vacations there with his mother.

Image: wikipedia/Michael Petzet, Ludwig II and his castles.

The dream of many Lechtal residents: to be able to live off the interest

In addition to building solid houses, many of the Lechtal merchants who had returned to the valley, most of them fabulously wealthy, wanted to put their capital to work for them. They wanted it to earn interest and ensure a peaceful, reasonably luxurious retirement in elegant surroundings. Since banks and savings banks did not exist then, the newly wealthy Lechtalers entered the money-lending business.

The Lech Valley as the Bregenzerwald's source of capital

The Lech Valley's money lenders first turned to the neighboring Allgäu region, where they offered loans at interest rates averaging between 4% and 4.5%. The first documented money transaction between a Lech Valley moneylender and the Bregenzerwald dates back to 1729. This was even though the journey to the Bregenzerwald was very arduous, as the Tannberg had to be crossed on steep mountain paths.

The Kanisfluh is the dominant mountain range in the central Bregenzerwald region. Just 200 years ago, this gently rolling landscape was a “hunger zone” where many farming families could only survive with financial assistance from moneylenders in the Lech Valley. Image: Wikipedia

The Lechtalers arrived in the Bregenzerwald at just the right time. In the second half of the 19th century, in particular, more and more farming families fell into poverty. The main reason for this was the Alemannic real division, whereby all heirs to a farm received an equal share of the land. This led to a fragmentation of land, and many families could barely feed themselves from the yield of their land.

The Bregenzerwalders appreciated the Lechtalers' favorable interest rates and the fact that the capital was not usually called in. And so the debts were often passed on from one generation to the next for decades, as "only" the interest had to be paid. The farmers could talk to their lenders even if they had difficulties paying the interest. Even the great farmer-poet Franz Michael Felder was a 'customer' of the Lech Valley moneylenders.

Franz Michael Felder, the “peasant poet” of the Bregenz Forest. He fought alongside the farmers against exploitation by the “cheese baron” Gallus Moosbrugger. And he was glad to have credit from the fair money lenders in Lechtal. Image: Wikipedia

Elisabeth Maldoner, the richest woman in the Lech Valley of her time

Here, too, are glorious examples of the humanity of Lechtal moneylenders. At that time, the richest woman in the Lechtal was Elisabeth Maldoner, known and admired in the valley as “rich Lisbeth.” In 1847, she owned nearly 300,000 guilders from her father's business.

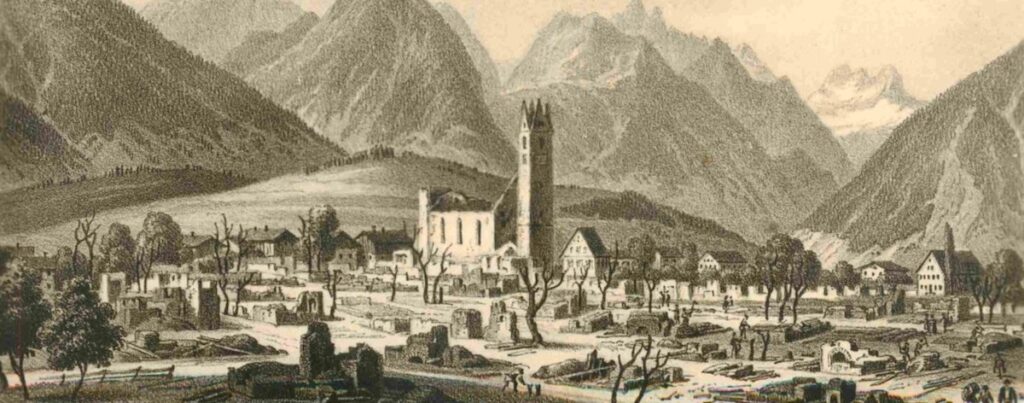

Elisabeth ‘Lisbeth’ Maldoner was one of the legendary, fabulously wealthy women of the Lech Valley. She lent money on a large scale, but was greatly appreciated by everyone for her humanity when collecting interest. She also helped the people of Oberstdorf rebuild their homes after the devastating village fire with generous loans. It is said that she ultimately even waived repayment of tens of thousands of guilders. Image: Wunderkammer Elbigenalp

The loan capital she granted rose by 112,864 guilders to 260,650 guilders between 1831 and 1847. "Rich Lisbeth" became famous when she made the reconstruction of Oberstdorf possible with considerable money. Within four hours on May 6, 1865, 146 of the 316 houses were burned down. The church, school, town hall, all bakeries, and shops were reduced to rubble and ashes. Presumably, she and her descendants waived a considerable portion of the capital repayment in the following years. She instructed her "interest collectors" to show consideration in complicated cases regarding interest payments. Moreover, the gentlemen were sometimes allowed to waive interest payments altogether.

So how much is around 300,000 guilders worth in euros? The newly built “doctor's house” in Holzgau, financed by wealthy returnees, cost 1,671 guilders at the time. Mrs. Maldoner therefore owned 156 doctor's houses. Based on today's construction costs of around 500,000 euros for such a house, Lisbeth Maldoner owned 78 million euros at the time.

Anna Knittel was born in Obergiblen-Elbigenalp.

On July 28, 1841, Maria Anna Rosa Knittel was born as the second of four children to Joseph Anton Knittel and his wife Kreszenz, née Scharf. She was born into a family that was not particularly wealthy, but prosperous by the standards of the time. Her father was a gunsmith and ran a small farm. One of her great-uncles was a famous painter who had achieved fame and glory in Italy as a self-taught artist. And one of her uncles was a sculptor in Freiburg im Breisgau. Thus, little Anna Knittel was practically born into the world of art.

Two personality traits complemented her family background. These traits would have a decisive influence on Anna Knittel's future life: her courage in twice leaving the nest and her determination to become an artist and lead an emancipated life as a woman.

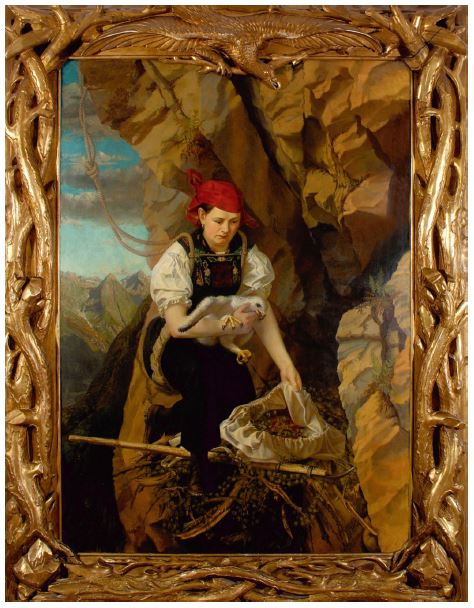

Anna Stainer-Knittel's self-portrait depicts her second descent to the eagle's nest in the Saxerwand in the Madaun Valley.

While Anna Stainer-Knittel's existence as a painter has received little attention to date, the character of Geierwally has remained popular in film, theater, and popular culture. Her alter ego is, therefore, both a blessing and a curse for her. She always played down her courageous action in the eagle's nest and did not attach much importance to it.

On the occasion of the remake of the novel Geierwally by Tyrolean artists, I want to use my blog to bring the courageous artist Anna Stainer-Knittel out from behind the 'Geierwally curtain'. It has obscured an artist who left behind a significant body of work for a long time. At the same time, I would like to describe the social, cultural, and economic circumstances that influenced her and with which she had to live. In a sense, it is a journey through time in the second half of the 18th century, using this admirable woman, who is legendary in Tyrol, as an example. If you don't want to miss an episode, subscribe to this blog.

Author

Werner Kräutler

Werner Kräutler