GEIERWALLY

The Myth

Daring back then, significant today.

MYTH

FROM BOOK TO BESTSELLER

PODCAST IN GERMAN

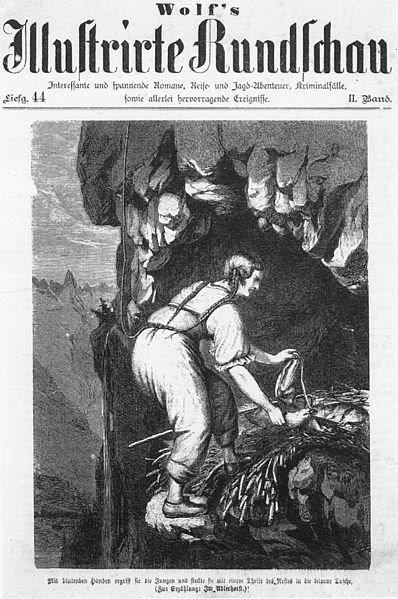

THE NOVEL AS A TEMPLATE

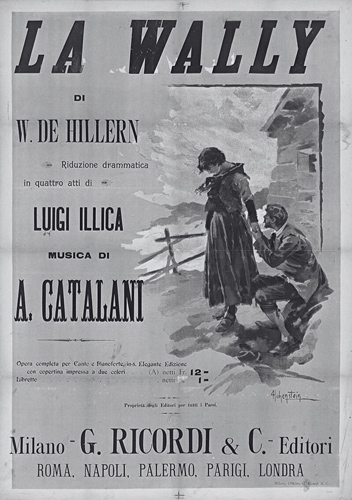

In 1873, Wilhermine von Hillern turned the story into a dramatic regional novel that has been filmed several times and has also been adapted for the stage numerous times.

MOVIES

„Die Geierwally“ has been filmed at least seven times. The movie adaptations range from the silent film era to the 2000s and reflect how strongly the material from Wilhelmine von Hillern’s novel of the same name (1873) has influenced German-language cinema.

1921

The first film adaptation, starring Henny Porten, was a silent film considered a classic of early German cinema. Porten established „Die Geierwally“ as an essential literary drama in cinema.

1940

The first sound film, directed by Hans Steinhoff, was released around 1930. In 1940, Steinhoff’s version followed, with Heidemarie Hatheyer in the lead role, as an elaborate Nazi-era production. The historical film adaptation with Hatheyer had a production budget of around 1.7 million Reichsmarks and was a clear commercial success.

In 1956, Barbara Rütting was given the lead role and gave a convincing performance in the Heimatfilm style of the 1950s. It is considered a solid addition to the Heimatfilm genre. It was the first color version to be released in Germany and Austria and was later distributed on video.

1988

Walter Bockmayer’s Geierwally is a parody of the 1980s. Deliberately satirical and garish, it remains a cult object to this day, but was not taken seriously as a film version.

2005

It was not until the TV remake with Christine Neubauer in 2005 that a modern „Heimatfilm“ adaptation was made. The fifth serious adaptation of the novel was conceived as a TV Heimatfilm, but received poor reviews.

The French-Italian version is less well-known but a free adaptation with the international title La Louve blanche.