GEIERWALLY

The Reality

Anna Stainer-Knittel.

TRUTH

CONTENT

About childhood and the eagle's nest in the Lech Valley

Anna Stainer-Knittel, later known as the "Geierwally," was born on July 28, 1841, in Elbingenalp, a village in Tyrol’s Lech Valley. The second daughter of gunsmith Joseph Anton Knittel and his wife Kreszenz, she had an older sister, Theresia Carla, a younger sister, Johanna, and a brother, Johann.

From a young age, Anna demonstrated exceptional artistic talent, often caricaturing classmates and teachers, trading her drawings for holy pictures. This early display of creativity and business savvy caught the attention of her father, who enlisted lithographer Johann Anton Falger to mentor her. Falger, who had studied in Munich, ran a local drawing school and took Anna under his wing. However, while her father supported her ambitions, her mother saw painting as a “breadless pursuit” and wanted her to follow the conventional path for women.

Despite her mother’s disapproval, Anna’s artistic talent had deep roots. The Knittel family had a rich history in the arts and crafts, with her great-uncle, Joseph Anton Koch, gaining recognition as a landscape painter. Her father, eager to nurture her potential, took Anna on trips to Freiburg and Mühlhausen, hoping to secure her an apprenticeship, but his efforts did not bear fruit. Nonetheless, these experiences inspired Anna and marked a turning point in her life.

Growing up in the Lech Valley, Anna balanced household chores, farming, and fieldwork with her passion for drawing. On rainy days, she would sketch designs for clothing and embroidery, while quietly nurturing the artistic aspirations that would shape her future.

1859: The eagle's nest and the beginning of a legend

At just 17, Anna Stainer-Knittel faced a challenge that would become a lifelong legend. Her father, a gunsmith and passionate mountaineer, had spotted a golden eagle nesting in the "Saxerwand" cliff. Eagles were common in the Lech Valley and were fiercely hunted to protect livestock. When no young man volunteered to descend to the perilous nest, Anna, with remarkable courage, stepped forward to take on the dangerous task.

With her father standing below, rifle in hand, ready to defend her from the adult eagles, Anna was lowered down the steep rock face by an experienced marksman. Armed with a hatchet, she expertly hooked herself onto the nest, retrieved the adult eagle her father had shot the night before, and secured the live eaglet. Her father later raised and sold the young eagles to falconers, and though the story spread through the valley, it went largely unnoticed by the media.

TrainING as a painter in Munich

Anna's journey to Munich began not with a decision, but with a chance encounter. While baking bread at home, she saw a gentleman with an artist's hat—Tyrolean painter Mathias Schmid—who, along with teacher Anton Falger, recognized her talent and encouraged her to pursue art. After much family discussion, Anna traveled to Munich with her father in October 1859, marking the beginning of her artistic training.

Accepted as the only female member of the "Verein zur Ausbildung der Gewerbe" (Association for the Training of Trades), Anna's admission to the academy was exceptional for women at the time. She started with contour exercises and plaster models, soon progressing to portraiture. Despite hardship—hunger, homesickness, and financial struggle—Anna’s resolve grew stronger, and she began to assert herself in the male-dominated art world.

Supported by patron Joseph Anton Schwarzmann and friends like Mathias Schmid and Moritz von Schwind, Anna’s work flourished. She visited the renowned Karl von Piloty’s studio, which deepened her admiration for art, despite making her feel small in the face of such greatness. Throughout her studies, she painted genre works, portraits, and even ventured into female nude studies, defying the norms of the time. Her self-portrait from this period, simple yet strong, reflects her determination and unbroken will.

After several years of study, Anna returned to the Lech Valley, exhausted but transformed. Though initially misunderstood by her family, her artistic growth was undeniable, with her study sheets pinned on the walls as proof. The former "Geierwally" had proven herself in a world where female artists struggled to be seen.

The Geier-Wally LEGEND

In the summer of 1862, Anna became the subject of local legend. The press dubbed her "the one with the vulture" after the daring eagle rescue, later coining her the "Geierwally." Wilhelmine von Hillern later turned Anna's story into a novel, Die Geier-Wally (1873), romanticizing the tale with a dramatic plot and heroine, though von Hillern never consulted Anna. While the novel’s success fueled her fame, Anna found the fictionalized portrayal alienating, feeling distanced from the exaggerated character.

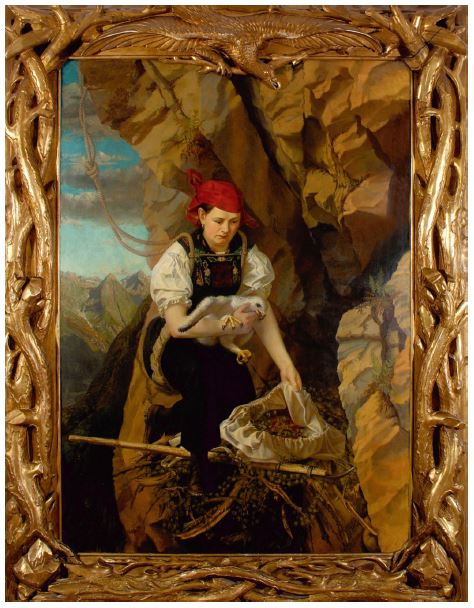

Despite her discomfort with the myth, Geierwally became widely popular, adapted into theatre, opera (including Alfredo Catalani’s La Wally), and film. The novel blurred the lines between fiction and reality, a confusion that Anna found challenging. To reclaim her narrative, Anna created her own version of the eagle's nest removal, a self-assured and detailed work that she completed with great effort, traveling to Elbigenalp for on-site studies. Though the painting was damaged in transit, it became one of her most significant works, showcasing her artistic vision and resilience.

‘The Large Eagle Painting’, self-portrait from 1864

Life and Work in Innsbruck

Before she ever set foot in Innsbruck, Anna Stainer-Knittel longed to build a life there. Hailing from the remote village of Elbigenalp, she dreamed of making a name for herself in the Tyrolean capital. However, after returning from Munich, she lacked the means to take that crucial step. While still in the secluded Lech Valley, Anna worked tirelessly on her artistic career, using limited resources but boundless ambition.

In the spring of 1863, Anna painted a self-portrait in festive Lechtal costume. The detailed Biedermeier style, showcasing velvet, embroidery, and shiny accessories, exuded pride and self-confidence. The portrait was acquired by the Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum for 44 guilders, opening the door to her long-awaited future. “Yay! Now we’re going to Innsbruck!” she wrote in her diary, her first earnings enabling her move to the city.

That autumn, Anna settled in Innsbruck and took on commissions, including portraits of Archduke Karl Ludwig and Field Marshal Radetzky. Her talent quickly gained attention among the city's bourgeois society, and she felt she had arrived. The city offered not only artistic opportunities but also warmth and new connections. With support from friends like painter Mathias Schmid and Dr. Brauner, who found her accommodation, Anna could finally devote herself fully to her art.

Innsbruck became a place of self-realization for Anna. She worked with discipline and sensitivity, earning praise for her finely composed portraits and detailed paintings. But soon, landscape painting captivated her. The mountains, valleys, and flora surrounding Innsbruck became new sources of inspiration. Her sketchbooks from this period reveal a keen eye for detail and a growing maturity.

In Innsbruck, Anna emerged as an independent artist. She was not content to paint in the shadow of others; instead, she developed her unique style. Her courage to leave the valley and earn a living as a female artist in a male-dominated world set her apart. The city, to her, was not just a place to live, but the fertile ground where her talent, freedom, and vision flourished.

Love and Family

In the spring of 1866, Anna lived in a small apartment on Innsbruck's Innrain. There, fate would lead her to an unexpected encounter. A young plaster mould maker had recently moved in across the hall. Known for his fine singing voice, Engelbert Stainer quickly captured the neighborhood’s attention. One evening, after hearing him sing, Anna mockingly commented, "You call that beautiful? He sounds like broken crockery!" Unbeknownst to her, Engelbert had overheard.

A few days later, Anna received a letter addressed to "the man across the hall." Curious, she knocked on his door. What followed was a surprise — a tall, slender man greeted her with warmth and politeness. Despite her usual confidence, Anna was caught off guard. "So, now my destiny has come to me," she wrote later. "I felt it with horror — this or no one."

Their love story blossomed quickly. Anna was drawn to Engelbert’s determination and work ethic. A self-made man, he had cared for his sick father and learned plaster moulding against his initial wishes. Their connection deepened, and soon they were engaged. However, their love faced challenges. Engelbert confessed to having fathered an illegitimate child. Despite this, Anna stayed by his side, defying her parents' objections. Eventually, they wed on October 14, 1867, after her father reluctantly gave his blessing.

Their honeymoon was modest, but their return to Innsbruck marked the beginning of a new chapter. They settled into a small, humble home, and their family soon grew. Business was tough, and the winters were harsh, but together, they built a life full of love and creativity.

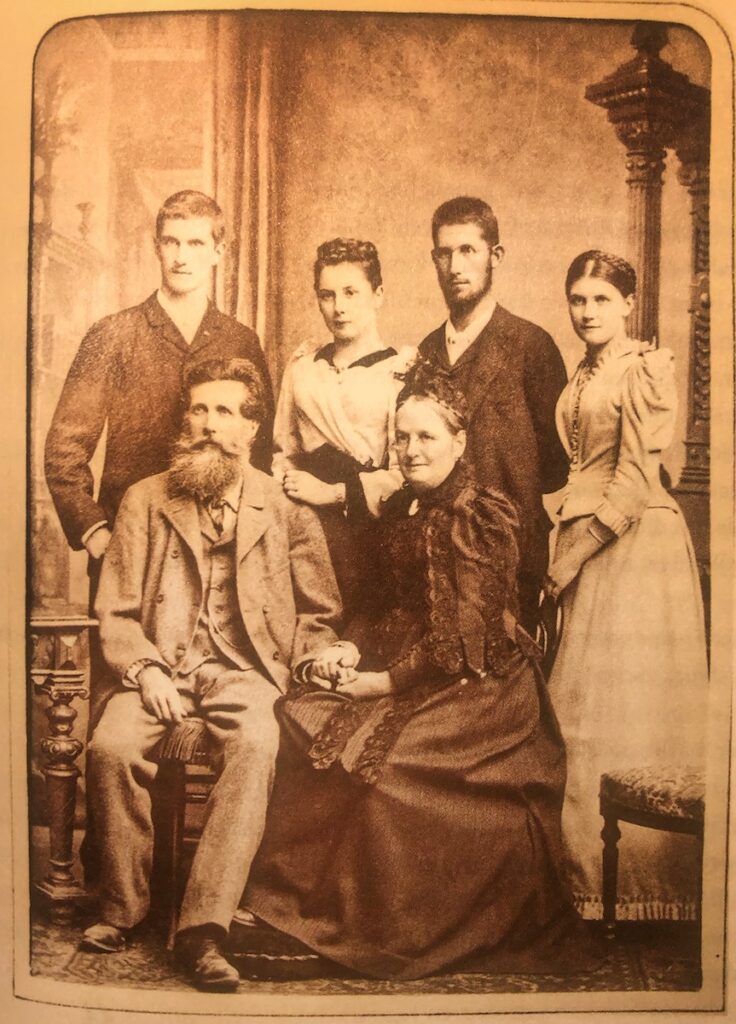

Anna and Engelbert had four children. Their eldest son, Karl, studied medicine, while Leo trained in Berlin and later took over the family business. Rosa attended a sewing school in St. Nikolaus, and their youngest daughter, Emma, followed in her sister’s footsteps.

Anna and Engelbert Stainer shortly after their wedding in 1867

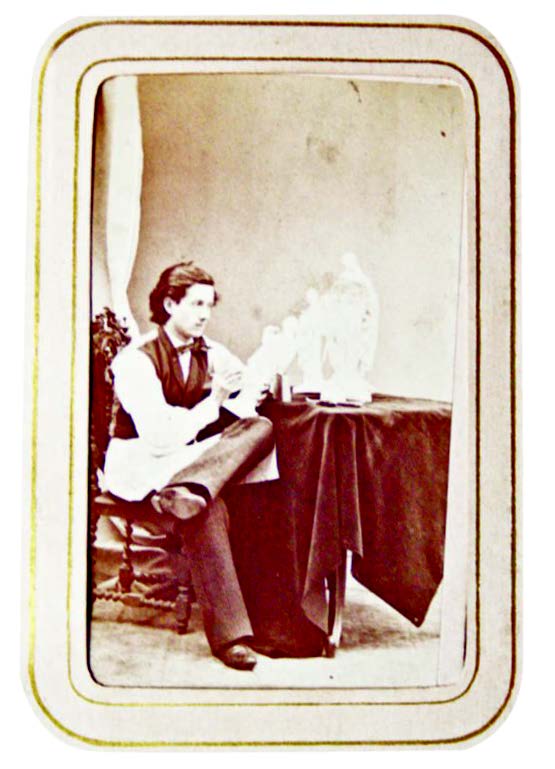

Plaster mould maker Engelbert Stainer

The Stainer-Knittel family in a family photo from 1890. In front are Engelbert and Anna, behind them from left to right: Leo, Emma, Karl and Rosa.

‘My painting seems to have come into fashion.’

The 1870s marked a pivotal period in Anna Stainer-Knittel’s artistic journey, particularly during the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair. This global event, held for the first time in a German-speaking country, brought together the world’s technical innovations, cultural diversity, and artistic creativity. Seizing the opportunity, Anna submitted her work to the newly created section for women’s art, hoping to face less competition. However, the overwhelming number of submissions almost caused her painting to go unnoticed.

It was Franz Migerka, a ministerial councillor and passionate advocate for women in the arts, who recognized the value of her work. Rather than returning the piece, Migerka ensured it was displayed in a parallel exhibition organized by the Miethke Art Gallery at the Künstlerhaus on Lothringerstraße. Though her painting could not compete with the grandeur of Hans Makart’s main exhibit, it caught the eye of an English collector who purchased it for 50 pounds sterling — one of Anna's first major sales. This success brought much-needed financial relief to her family.

However, despite the triumph, the experience in Vienna proved exhausting. The bustling city, coupled with health issues, left Anna and her husband, Engelbert, physically drained. Upon their return to Tyrol, Anna had to take a break from painting to recover, finding solace in the quiet of the Lech Valley and simpler fieldwork.

Once restored, Anna entered a highly productive phase of her career. Together with Engelbert, she launched a new business venture: painted alabaster figurines and floral souvenirs. These sold rapidly, particularly during the Passion Play season in Oberammergau. Moving the family to a more centrally located home on Rudolfstraße in Innsbruck further boosted sales, making their business more successful.

During this time, Anna worked relentlessly, often painting late into the night. Her dedication took a toll on her health, but her efforts began to pay off. Her work found a steady stream of buyers, and Anna gradually gained financial independence, even insisting on opening her own savings account — an exceptional act of self-determination for a woman of her time.

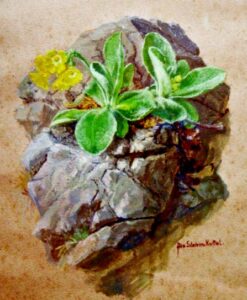

Plate with alpine flower motif, 1891

Family life at their new home, the "Leishaus" in Innsbruck, was full of activity. Her children were growing: Karl attended secondary school, Leo completed his apprenticeship, Rosa blossomed into a young woman, and the youngest, Emma, became a confident teenager. Yet beneath the surface of this bustling household, a dark cloud began to form.

On a trip to the Igler Alpe, Anna and Engelbert met a young man named Adolf Ortler. Initially welcomed into the family, Ortler appeared to be an ideal match for Rosa, who had grown into a tall and graceful young woman. After a few outings, an engagement followed. But what seemed like a stroke of luck quickly unraveled when Ortler, now a pharmacist in Kössen, began an affair while refusing to end his engagement with Rosa. Heartbroken, Rosa ended the engagement — a bold decision that profoundly affected her. The emotional toll manifested physically as Anna watched her daughter struggle with loss, leading to a decline in her own health.

Amidst these personal trials, Anna and Engelbert marked a bittersweet milestone: their silver wedding anniversary in October 1892. The couple traveled through northern Italy, including Trento, Riva, Verona, and Venice. Anna’s poetic account of the journey reflected a deep emotional resonance. The moment she first saw the open sea at the Lido was transformative, inspiring in her a contemplative understanding of life’s fleeting nature. This experience brought her both solace and strength, marking a significant moment of self-reflection.

But their happiness was short-lived. Upon returning to Innsbruck, Rosa’s health sharply declined. After a stay in Merano, she returned frail and weakened, an image that haunted Anna: “With what heartache I saw her coming up the stairs.” Rosa’s condition worsened rapidly, and despite the best efforts of doctors, she passed away shortly after, in the family home. Her untimely death left an indelible mark on Anna, who faced the loss with the strength and fragility of a mother who had already endured much.

Anna continued to paint and sell her work after Rosa’s passing, using art as a means to process grief and find hope. Her paintings became a way of preserving beauty, even in the darkest hours. Despite this, the pain of Rosa’s death remained a wound she revisited often in her letters, a shadow that never fully lifted.

Rosa with flower basket, oil on canvas

Her last years

As the years passed, the Stainer-Knittel family underwent significant changes. After the children had grown and moved away, Anna and Engelbert remained in their small apartment on Templstraße 13 in Innsbruck. They continued to visit Engelbert’s childhood home in Pfunds and reminisce about old memories. Meanwhile, their son Leo took over the family shop on Maria-Theresien-Straße, and Karl, having completed his doctorate, moved to Wattens in 1894 to serve as the community doctor.

On September 13, 1903, Engelbert passed away after years of struggling with a chronic stomach ailment. Anna, though devastated, continued to paint, splitting her time between Wattens and Innsbruck. In 1911, an exhibition dedicated to Anna was held at the Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck, marking her continued prominence in the local art scene.

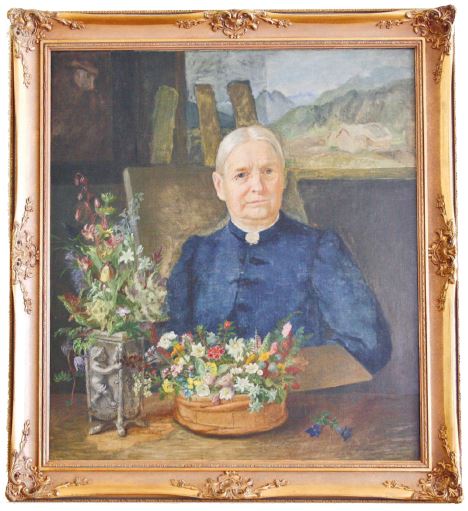

Anna’s last self-portrait, painted in 1915, is a poignant reflection of her artistic maturity and introspection. Unlike earlier portraits, where she donned traditional Tyrolean dress, she is depicted in a simple blue dress, exuding an air of calm composure. On the table before her, a still life of wildflowers — a recurring motif in her work — captures the viewer’s attention, reinforcing her connection to nature and her art.

Large family in Wattens: Leo and Karl in the middle at the back, Anna sitting in front, approx. 1910

The portrait itself is striking: Anna, holding a palette in her left hand, gazes directly at the viewer with quiet intensity. The unfinished quality of the painting, particularly the raw surface and unfinished background, gives it a modern, open feel, almost as if the artist was still in conversation with her work — and with us. The juxtaposition of detail and imperfection suggests a deliberate break with tradition, a final commentary on her artistic journey.

Anna never completed this portrait. In February 1915, she fell ill with pneumonia. Despite her age and weakened heart, she could not recover. Anna Stainer-Knittel passed away on February 28, 1915, at the home of her son Karl in Wattens.

Her last self-portrait remains a silent legacy, an image of an artist who fought for her art, her family, and her independence. With a steady hand, a fierce mind, and an eye for detail, she preserved the beauty of life and death in her work, leaving behind a legacy that endures in both her paintings and her story.

Anna Stainer-Knittel in her last self-portrait, 1915

All content on this page refers to the work ‘Anna Stainer-Knittel Malerin’ published by Universitätsverlag Wagner.

LITERATURE

Anna Stainer-Knittel Malerin

Nina Stainer

The most comprehensive work on the life of Anna Stainer-Knittel is available as a book and e-book.

Nina Stainer

The most comprehensive work on the life of Anna Stainer-Knittel is available as a book and e-book.